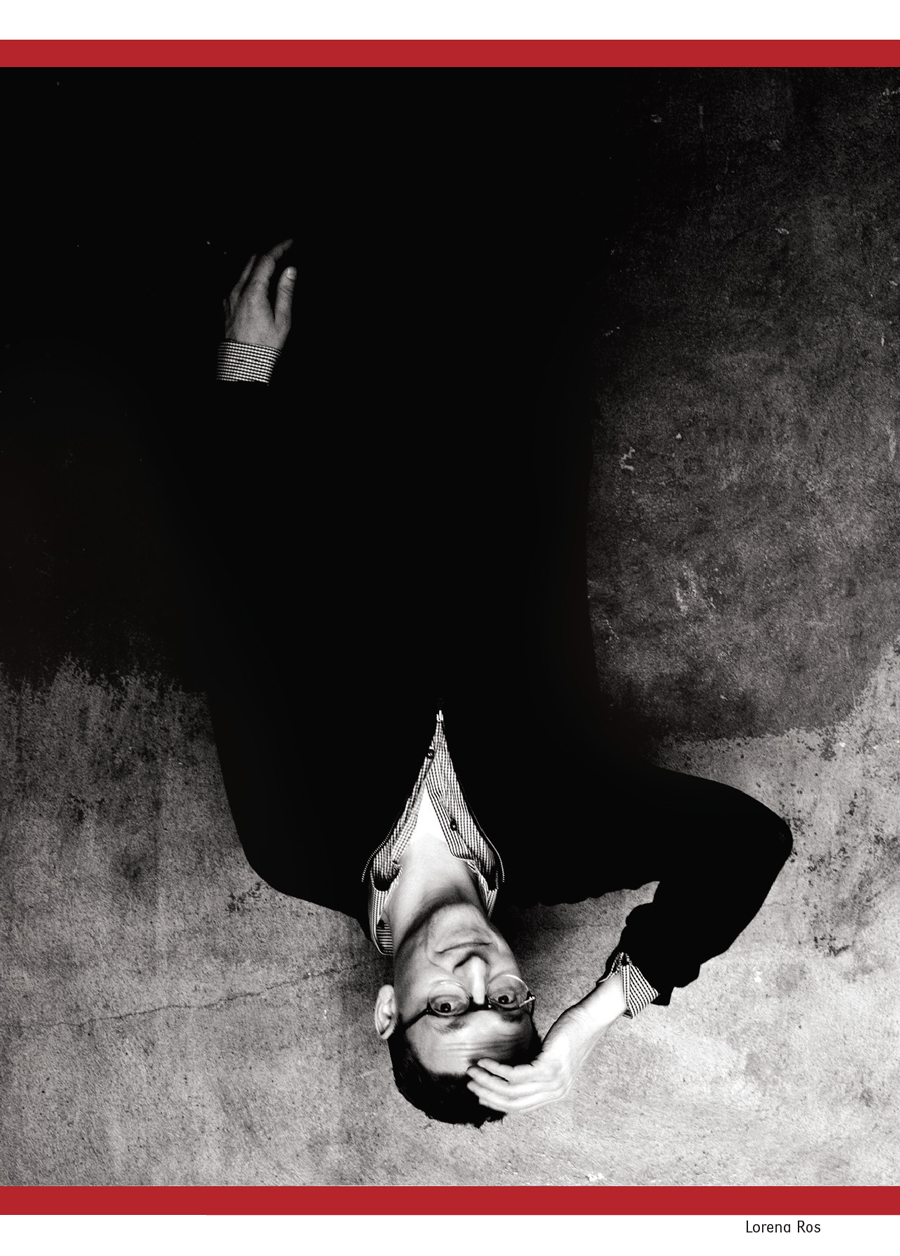

Benjamin Anastas

Benjamin Anastas might be literature’s most successful failure. From his first novel, An Underachiever’s Diary, to his recent memoir about going professionally, romantically and economically bust, he’s morphed from the Patron Saint of Slackers into the God of Misfortune himself. We visited Anastas on the flip side of the American dream so that he could shed some light on the darkness.

conduit: I love the moment in your memoir where your agent delivers the news that he’s sold your novel, but he won’t tell you for how much, as if the low figure is the ultimate tragedy. While, of course, we want to be paid for our work, there’s almost no mention on his part whether the book is good. It’s as if the work isn’t worthwhile in its own right.

benjamin anastas: I think it’s a mistake for writers to live in New York City because it’s too close to the industry. I wanted to come to New York when I got out of grad school in Iowa because I felt like I needed my horizons widened, I needed to live in a bigger place, I needed to live in a real city. I wanted to go to a place where I felt like I was seeing the world. New York can still make you feel like that, but too often it feels like a village where all anybody cares about is what they’re buying and what they can acquire and how much success they have. You’re constantly aware of how much other writers are being paid for their books and how excited everyone in publishing is about what everyone else is writing. One of the things that was disheartening about the experience with my novel was turning it in and hearing I was a genius, and then when the publishers started coming back with no offers, being treated like I was a nobody. Opinion in the industry can turn very quickly.

conduit: In the memoir, you sometimes sound as if you also were unhappy with how your novel turned out. Do you think it was a failure or did you just see it that way because of its reception?

anastas: Every time I approach a book it’s a real experiment. You never know whether it’s going to work or not. There were a number of ways to make that novel work, I just didn’t find them when there was still time to salvage it. I struggled with that novel for over fours years. I mean, really, really struggled. It was just an incredibly hard book to write. Hard in large part because what it was about. I was trying to reconstruct my maternal grandfather’s life in Prague and in Austria. He was an Austrian Jew who was born in Prague and had entered psychoanalysis in his early twenties—my grandfather had what we’d call now some pretty severe psychiatric difficulties. He managed to emigrate to the United States in 1938, partly through the help of the writer May Sarton, who he’d met at an inn in Grundlsee where a Viennese socialite held a cultural salon every summer. Anyway, my grandfather came to the States, met my grandmother, and started a family. He worked as an acoustic engineer and then ended up killing himself in 1966. His suicide really hung over my whole childhood, and in trying to reconstruct his early life, I was trying to write about him and trying to figure out who he was without confronting the real crux of the matter, which is the suicide. On a certain level, I was trying to save him. And I just felt oppressed by him and I felt oppressed by the whole responsibility. What I learned is that I’m not suited to write historical fiction. I picked this project that was so massive—it was greater than I was—and I felt that way the entire time. I lost touch with a lot of my instincts as a writer. Instead of just writing it as an essay, which would have made more sense, I wrote it as a novel and I got wrapped up in being faithful to the time period and faithful to the narrative that was his life. My instincts as a writer were undermined by the idea of my grandfather looking over my shoulder every day. I had pictures of him all over my study.

conduit: Would you say that in writing a historical novel, you were setting a new standard of truth for yourself? Just as with each novel a writer tries to aim higher than the last one?

anastas: I was definitely aiming higher, that’s for sure. At the Feet of the Divine was a very ambitious book. I wanted it to read as if it were a German language novel from the prewar period that had been rediscovered and translated into English. Awkwardly, too. I read a lot of Germanlanguage literature from that time and I based the style that I used in the book on all of it. Robert Musil, Stefan Zweig, writers like that. It’s funny, in some ways it worked, because now the novel only exists in the German language [laughs]. In some ways, I accomplished what I set out to do too well. But you know, I think that as a novel, the thing has fundamental flaws. I say that not necessarily because of the reception in publishing. I’ve had time to reflect on it now and I think I made a lot of rookie mistakes.